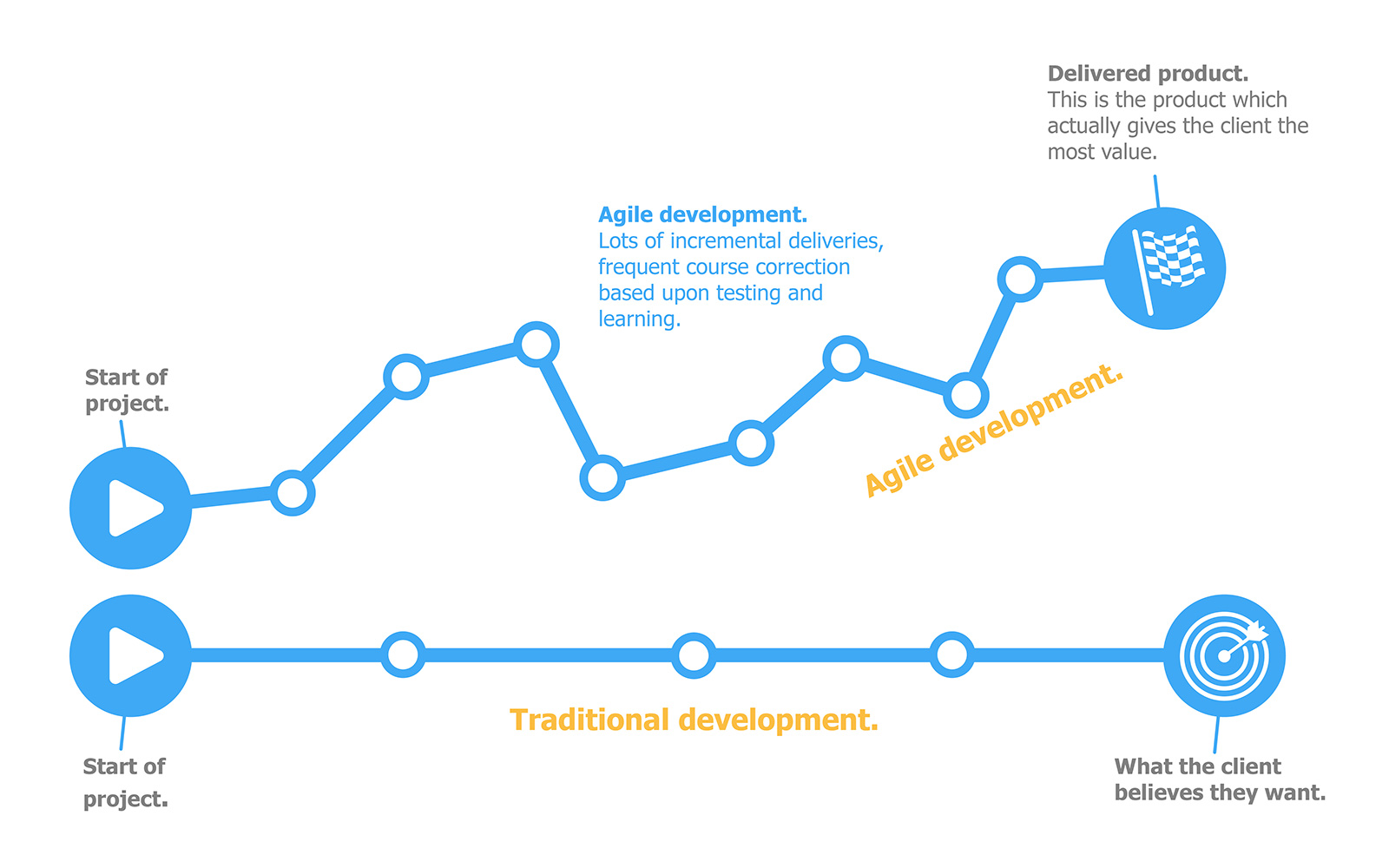

The Agile approach to product development arose in the Software industry and has been used very successfully by many software development teams since the 1990s (being formalised to some extent in the 2001 “Agile Manifesto”).

One of the key principles is that you cannot fully specify a software product, especially one with a user-interface element, at the beginning of a project. No-one knows (no matter how much they charge) what really works for users until users can actually use it! Instead the Agile mindset is to set the goal to be something small & usable, test it (if possible with real end-users), learn from what you discover and then fine-tune your direction based on what you learn. You then define another slightly more refined goal with more features, build that, test it, learn from it – and repeat until you get to a product that you can take to the market.

This does not mean that you set off on a development with no plan: you have a target that you are aiming for in the short term, and which is pretty well-defined, but you do also have a target in the longer term which you are aiming for; but in this case you recognise that you may end up aiming for a different target, depending on what you learn from the users as they try out your intermediate builds.

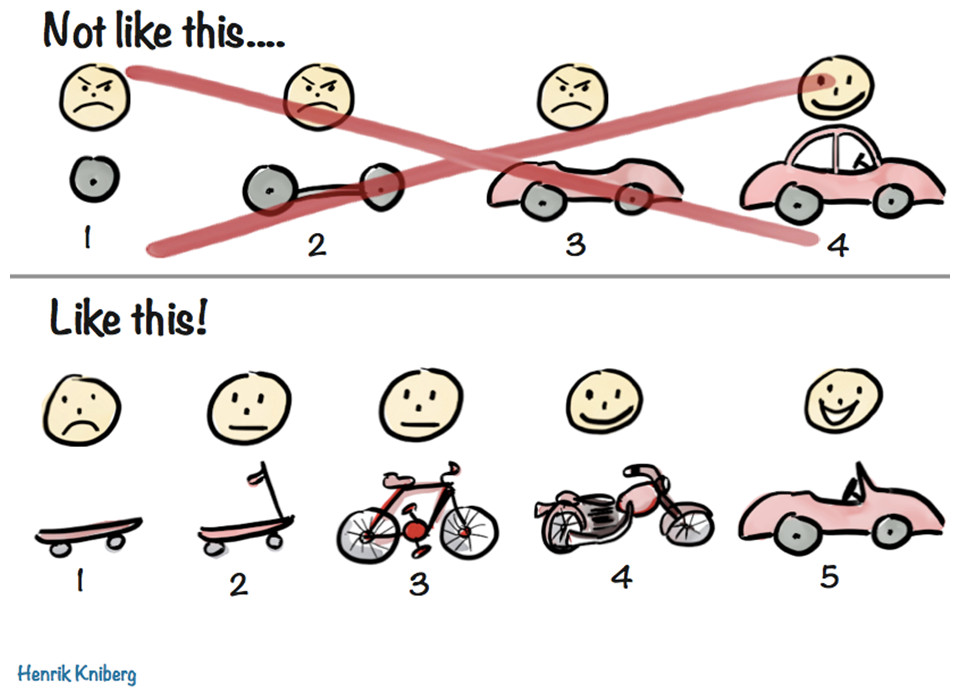

Sometimes the changes will just be tweaks – sometimes they will be quite radical. This was captured in a famous (in the Agile development community, at least!) graphic by the Swedish Agile Coach & writer, Henrik Kniberg (who has worked with very successful businesses such as Spotify):

While we agree with the simple sentiment of the cartoon and what it represents from an incremental improvement and viability perspective towards the developer’s end goal, we would take a step back and say that some users are actually happy and, in many cases, would prefer to stick with the simpler and often more reliable skateboard or bicycle. They may never opt and be willing to pay for the features and proposed convenience of this preconceived end goal.

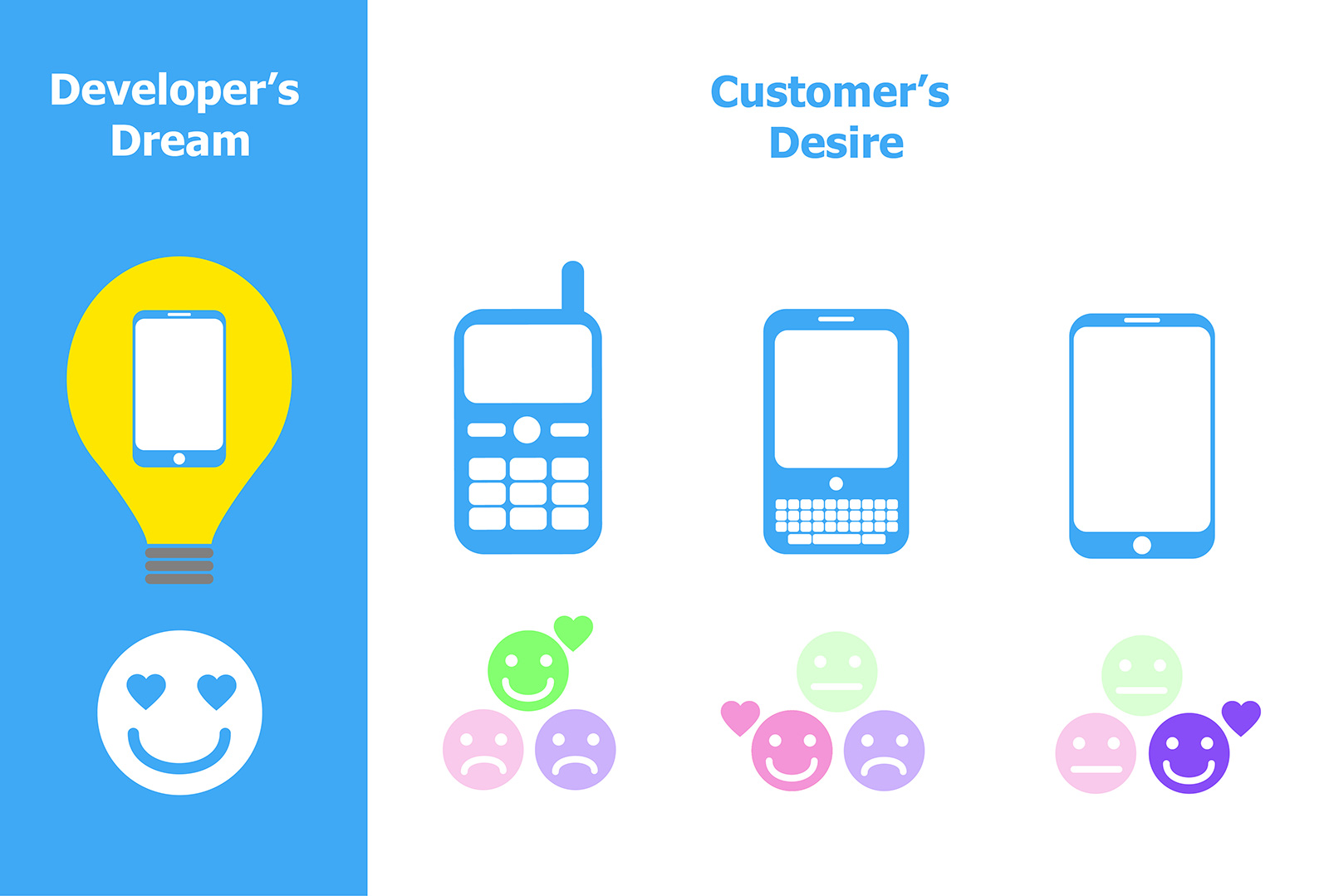

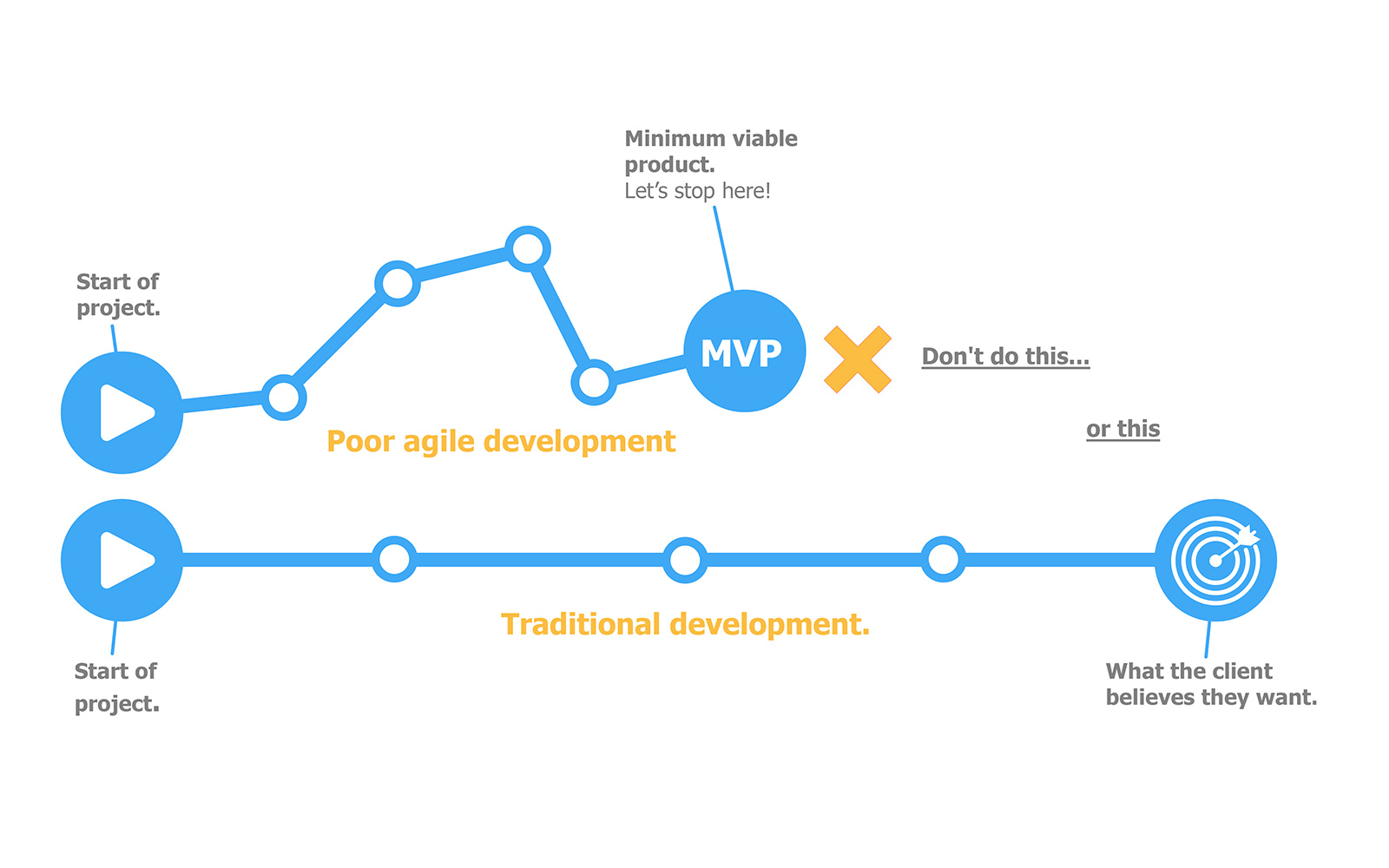

We feel our diagram below goes some way to capturing the challenge developers can face when they set out with preconceived dreams of what the consumer wants and, often more importantly, what they are willing to pay for. In reality, some customers will accept a more minimum approach to a design and features built into a product and you could end up alienating part of your market by adding too much complexity and cost into your device. This is where an agile approach can help you focus on what you need to do to attract the maximum users/buyers of your device.

(As further reading we would strongly recommend you take a look at Henrik Kniberg’s blog post on “Making Sense of Minimum Viable Product”: https://blog.crisp.se/2016/01/25/henrikkniberg/making-sense-of-mvp.)

So what does Henrik have to tell us?

Minimum Viable Product is a well-established concept in the Agile world of product design (hardware and software). As we work through an Agile development process, as we saw above, we keep on making things which are more refined than the previous version: we add features, improve performance, remove features which aren’t used, add more features, make the user interface less confusing, improve documentation… it’s all making the product better, incrementally. At some point, the argument goes, we get to a version where Marketing say, “Aha! We can sell this one now!” and it gets released to the market. That is what we call the Minimum Viable Product: it’s minimum – we have done as little as we can – but it’s viable – it is recognisably a product that people will pay money for (or use, at least: products aren’t always charged for, especially in the internet software world).

Of course that is not meant to be the end: the development team now get even more feedback from the new users, continue to learn what enhancements or modifications will make a better product (one that provides more value to the users), and keep on developing new versions. For a lot of commercial software (embedded or application), but particularly software delivered via the Internet, the following really is what happens: the product is continuously updated and released, becoming incrementally better and gaining new functionality as new requirements emerge.

The big problem is that for most customers and perhaps some non-institutional investors the phrase Minimum Viable Product does not convey that sort of picture! Instead they hear negatives. Minimum? That’s the least amount you could do, and that’s what you are offering me? Why should I accept that? Don’t give me the Minimum, give me the Maximum! And viable? You mean only just alive? Can’t you do better than that? When customers have these negative reactions they will then assume that the product design team are using “MVP” as a way to do as little as they can, and they fear being left with an unacceptable product.

We can argue that these are just semantics – we as a design and development consultancy know what MVP really means and that it is not the end of the journey but just an important waypoint. But words do matter, and Minimum Viable Product can be a difficult thing to sell to a customer. Not only that – if we only have one target, the Minimum Viable product, in our sights then we risk either aiming too high (where it is much more than a “minimum”) or not having a clear medium-to-long-term plan (where we really only have that minimum target and don’t have any plans to get beyond it).

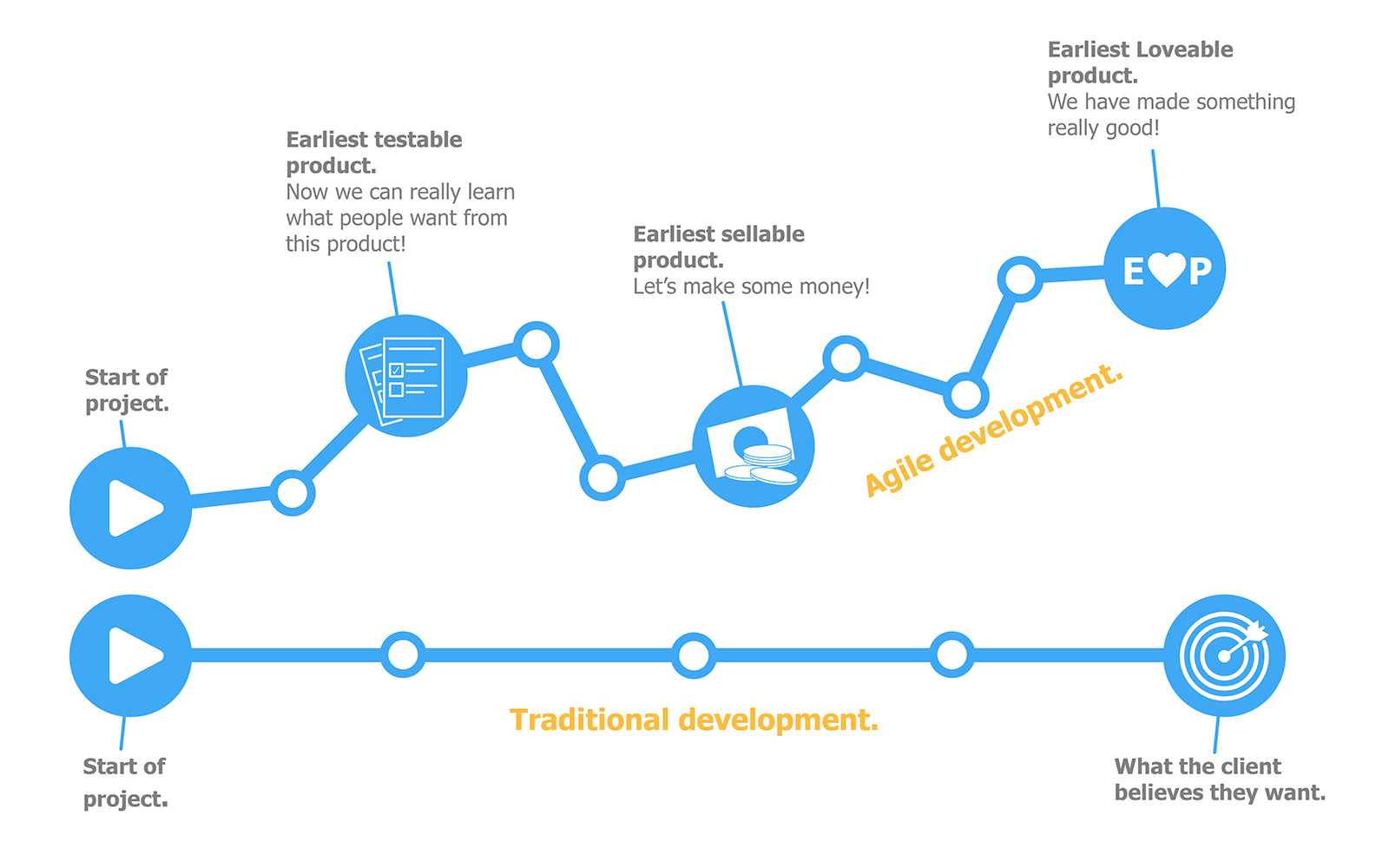

The way to address both these areas of concern, as suggested by Henrik Kniberg, is to stop talking about the Minimum Viable Product, with its negative connotations, and instead talk about some really positive things.

First – let’s not say minimum, which no one really wants: let’s say Earliest! Everyone wants something early. It’s good for the customer/user and good for the developers.

And let’s not talk about viable. Instead let’s ask what we gain by having this version of the product. And when we do that we realise that there is not just one target, there are at least three, which we can define: and that gives us a roadmap, which helps us avoid the perils of aiming too far or failing to plan for ongoing product development. The three targets we should think about are:

We will end our sermon here. Let’s stop talking about the Minimum Viable Product: let’s think about a product development roadmap which gives customers some more clarity about what the deliverables along the way will be, and helps give customers and developers a series of targets to aim at. Goodbye Minimum Viable Product – say hello to the Earliest Testable, Earliest Sellable and Earliest Lovable Products!